Resonating Across Time-Zones

He had started to learn English only at the age of ten. It is all the more remarkable that having arrived in Sixth Form, from Keio High School, 'the best school Japan', he improved his English to such an extent that he made the College final six, out of 250 native English speakers, in the Kenneth Clark Prize, a competition requiring particularly well-honed presentation skills. His chosen subject was the oldest standing tea house in Kyoto, Japan, his aim to explain the Japanese tea ceremony as a spiritual experience: an 'amazing accomplishment', wrote his Housemater.

Yasu is sixth-generation pupil at Keio, How significant is this for him? 'It helps me to be proud of my school...but this continuity does now shape me; more important is my own experience, and the excitement of my scholarship from Keio to Winchester'.

In front of a favourite restaurant named 'Torahige' in Hiyosh, Kanagawa

Energetic, organised and motivated he made time to found a Japan Society, to undertake community work, to co-edit the Winchester Journal of Economics, to write admirable essays on Quantative Easing, and to study topics ranging from behavioural economics, econometrics and circular and new capitalism, to climate change issues.

A particular achievement, much praised by his dons and his peers, was Yasu's Extended Qualification Project (EPQ) which focused on his detailed analysis of 'Manners Makyth Man." He was motivated by the similarities of the school's traditions and values to those of Keio, whose motto is 'to be a constant source of honourable character and a paragon of intellect and morals." He was rigorous and persistent in his research, gaining inspiration from Dr Mark Griffith from Oxford, Dr Hands and others in the Wykehamical community.

He begins by noting William of Wykeham's radicalism in selecting English for our motto, and not the 'high-status' Latin or French, of which both languages he would have had at least a working knowledge. Perhaps he decided, with Dante in his De Vulgari Eloquentia, that reality can be better expressed in one's native language; or perhaps the use of the vernacular simply reflects his own English background as the son of an 'upper-level peasant, a yeoman, from Wickham."

Riding the Tokyo-line train on the daily commute to school

In exploring what Wykeham meant by his motto, Yasu highlights his three purposes in founding Winchester (and New College): intercessionary, for his 'foundations to interecede on his behalf for his soul'd salvation'; scholastic, in order to give young people scholarships as a way of distributing his own riches to the poor; and thirdly, clerical, so that the beneficiaries of a Wykeham education ' repay their debt by serving their peers and nation.' The reason for intercession was possibly to highlight Wykeham as a pious Christian, but Yasu states that it was more likely the result of his devotion to the Virign Mark (to this day Winchester is formally called St Mary's College) than for any ecclesiatical ambitions; the scholastic element continues to be reflected in the school today in the scholarships awarded to Collegemen and the bursaries enjoyed by many pupils; whilst the clerical component, which in the 14th century was designed to nurture administrative skills for the running of the country by the clergy, now informs the political classes who long ago superseded their pious predecessors.

Yasu summarises his re-interpretation of the motto for today as 'Even if you were born into a wealthy family and get a good education at Winchester, this does not mean you can succeed in life without having Manners.'

In analysing the meaning of 'Manners', Yasu studied an article in The Wykehamist by HE Salter, who translated the motto into Latin as 'urbanitas componit homines': 'urbanitas' meant 'good manners' in the middle ages. This could settle the matter, but Thomas Chaundler, ex-Warden of New College, offered an alternative translation: 'mores componunt hominem': the word 'mores' introduces varied definitions ranging through 'moral habits', 'attitudes' and 'manners' to 'ways', 'charater' and 'behaviour'. All of these could imply a type of piety derived from Wykeham himself.

The definition of 'Manners' is therefore opaque, but Yasu argues that the Trusty Servant, arriving in 1580, 200 years after the founding of the College, highlights the virtues of the perfect servant as a template for the Wykehamist, and can therefore, though perhaps not in the moral sense, provide a clarity which 'correlates with the motto-meaning of "good manners".

Whether 'Manners' is defined in the moral sense, as is most likely in the 14th century, or is based more on good character, Yasu said his research gave him an 'interesting insight...that Wykehamists are not affected by the motto itself, but by the education or culture shaped under its influence'. He concludes: 'We might be advised to let ourselves be formed by the "Manners" that the school and Wykehamists established and have passed down for more than 600 years.'

Yasu goes on to state that the definition of Man is dervied from the Anglo-Saxon 'Mon' as a gender generic word, meaning 'human being'. This is corroborated by the Oxford English Dictionary. Those responsible could be led to conclude that, with the introduction of girls to the school, the motto can be left untouched.

The Middle English word, 'makyth' includes the concept of 'growing' and Yasu cites Div as an example of the making of 'Man', in contrast to Man being 'made' from exam results alone. In conclusion, he suggests that the concept of 'Manners' goes far beyond intelligence, and relates to a person's whole being, not just their achievements; this is somthing he has felt keenly throughout his year at Winchester. The motto 'is very much relevant today, and it will be relevant to Wykehamists in the future."

Div was a game-changer for Yasu. 'I had a lot of discussion classes which represented a big difference between Japand and England; in Japan, we are not good at expressing our opinions, even during discussions.' He was fortunate that he could offer views on one particular topic, the differences between Oriental and Western cultures and histories. Back at Keio, he has now taken up the challenge of introducing discussion groups.

He acknowledges that 'it was hard; it was not easy' when he first came to Winchester, owing to the language and to cultural differences. He made headway only by engaging with people during activities such as sport and music. He says that his House was welcoming, where he made many friends. He cites House lunch as important: 'I really enjoyed the time with teachers.' His Prefect was consistently kind to him and 'had his own confident way of dealing with people, including great kindness and steadiness.'

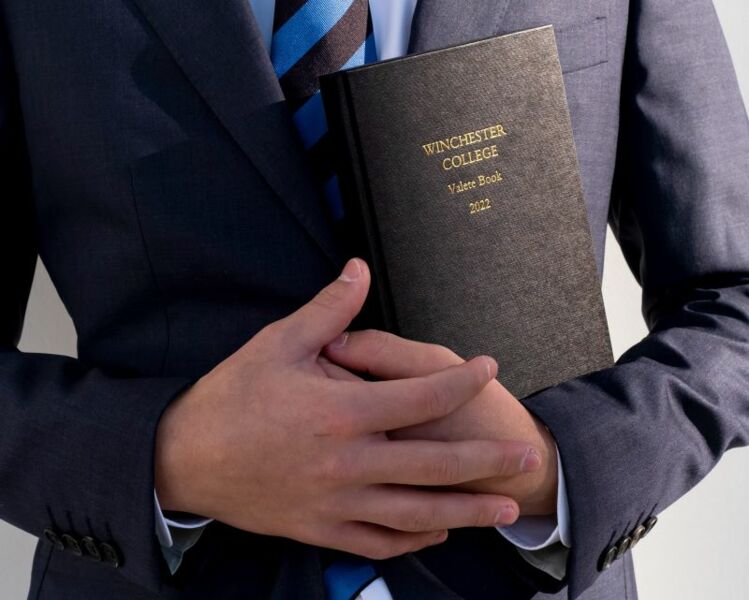

With a book given to leavers in which friends write messages

Yasu regarded Community Service as a great opportunity at Winchester, given there is little in Japan. He volunteered in a Primary School, assisting 'children to interact with nature, including trying to catch some fish in the river and study insects'. 'If they don't engage with nature,' he says ' they will never be interested in climate change' - another of Yasu's passions. He has initiated engagement with a Primary School in Japan.

Yasu reflects on his year: 'I loved my time at Winchester; it was completely different from my experiences in Japan - there were so many opportunities for me.' After leaving he was accepted as one of very few from secondary schools onto a Harvard College Project for Asian and International Relations. There, among other things, he heard from the Global President of Pfizer on how established procedures were compromised to speed up the production of a Covid vaccine. LGBTQ issues and gender inequality were also discussed - 'one of the bad traditions in Japan.'

What of career? 'I'm trying to find a way to contribute to society', says Yasu, 'but it depends on what I study at University.' He is interested in the provision of foreign language help for refugees. His div don's note is less equivocal: 'Yasu is a remarkable pupil, with leadership qualities, who could easily become an international figure of significance in his future life; any University is going to be taking a truly outstanding young person.'

We wait and watch.

Head back to stories

Head back to stories